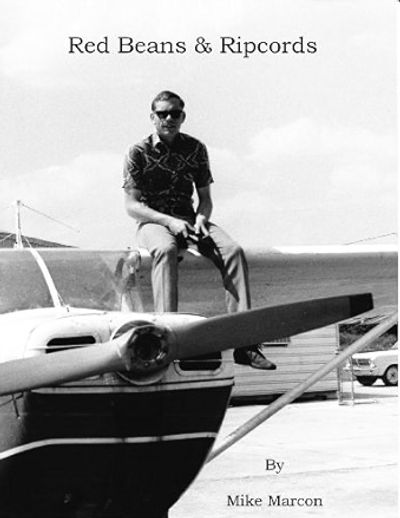

Red Beans & Ripcords Project

The Red Beans & Ripcords Project

Introduction

In the summer of 1962, I was 17 years old, and had been in the U.S. Army just long enough to complete basic and advanced training, jump school and then be assigned to my first permanent unit at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Late one afternoon, after evening chow, while laying on my bunk, half-asleep, staring at the ceiling, the thunderous sound of someone running up the wooden stairs of the old, two-story World War II era barracks that I called home grew loud in my ears. It was a buddy from the second squad downstairs coming to excitedly share some news.

He ran to my bunkside and told me that he was going to start classes at a sport parachute club on base to learn how to skydive the next week-end. He wanted to know if I wanted to join him. Without hesitation, I said I was in.

That would be the beginning of a long and exciting journey that would last for many years to come. The pursuit of the next jump, the next adventure, would become my life blood. I would come to know many colorful characters and personalities who jumped alongside of me, some of whom would shape my destiny.

The stories that I will serialize here and reprint on my website in the weeks and months ahead are from a book that I wrote many years ago. Now, nearly fifteen years later, I have come to realize that there were quite a few incidents and characters that I had left out of the original stories. So, I decided to revisit every story and rewrite them, making them more complete and interesting. I’ll also be adding some new stories to the mix as I go along. I don’t intend to turn these stories into another book to sell. I am revamping the stories for my own pleasure, and hopefully, you’ll get a kick out of reading them.

The stories you will read mostly take place in southern Mississippi and south Louisiana in the mid-to-late Sixties. And some of what you will read is aimed squarely at “whuffos” - as in “Whuffo you jump outta them airplanes?"

INSTALLMENT ONE

They’re called “Skydivers” today. But, in the day, we were called “Sport Parachutists.” I prefer the simple term, “jumper.” The places we jumped were called “Drop Zones.” This is where you landed when you jumped. A drop zone’s atmosphere and personality was usually due to whoever owned or operated it and the way they conducted business. In many cases, club drop zones weren’t located on airports; they were simply cow pastures large enough to accommodate a small airplane’s comings and goings. But the real “flavor” of a drop zone came from the various personalities that showed up on the weekends to jump and hang out. Saturday mornings on a drop zone anywhere might see people showing up in their cars, vans, campers or motorcycles, and the life they lived off of the drop zone could range from that of a doctor or a bricklayer or a deep sea salvage diver or a beautician; but for the time they were there jumping and partying alongside of you, they were skydivers and that was all that mattered.

At the start of the Twentieth Century, a very few kindred souls like Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick were the real pioneers of skydiving. She was nicknamed 'Tiny' as she weighed only eighty-five pounds and was four feet tall. At the age of 15, in 1908, she first witnessed Charles Broadwick of The World Famous Aeronauts Show, parachute from a hot air balloon, and she decided then and there to join the travelling troupe and become an aerial stunt performer. Among her many achievements, she was the first woman to parachute from an airplane on June 21, 1913, jumping from a plane built and piloted by Glenn L. Martin, at 1,000 feet over Griffith Park in Los Angeles. She was also the first woman to parachute into water.

Other “pioneers,” mostly ex-soldiers, particularly after World War II, began jumping for sport in small groups at military bases and at civilian airfields scattered around the country until the early 1960’s when the sport really began to grow in popularity. I was initiated into the sport at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the home of the 82nd Airborne Division. I made a three sport jumps there before being transferred to Germany where I made no jumps at all, not even troop jumps, for several years.

In 1966, at the end of my first tour in the military, I decided to get out and follow my passion, sport parachuting. At first, for a few months, I worked at minor part-time jobs to support myself, and then I was offered a job at Southern Parachute Center in Hammond, Louisiana, where I threw myself head-long into what, today, is called “skydiving.” Let me give you a look at the state of skydiving in the early-to-mid-1960’s. For many jumpers then, especially civilians, it went something like this.

In 1957, the first commercial skydiving schools began to appear, but these operations were few and far between. At the time, a loosely organized body of skydiving devotees called, The National Parachute Jumpers-Riggers, Incorporated, was established to attempt to create some safety standards for those participating in sport parachuting. That group would later become the Parachute Club of America. The PCA renamed itself the United States Parachute Association in 1967. Beyond promoting skydiving as a safe sport, some of its primary missions were to create and enforce basic safety standards for jumpers and to represent sport parachutists in the ever burgeoning world of federal aviation regulations. However, up until about 1965, whether or not you were a member of any organization regulating skydiving was of little consequence.

In time, commercial skydiving centers and various sport parachute clubs begin to require a USPA membership in order to participate. Jumpers had started to realize that the Federal Aviation Administration was increasingly looking harder and harder at regulating sport parachuting, and skydivers knew that they needed a national lobbying body to keep from being regulated out of the sky. The USPA also knew that skydiving was quickly gaining popularity and more stringent training guidelines and safety regulations were necessary if the sport was to survive.

But prior to 1965, it was pretty much a whatever-you-could-get-away-with affair. Parachutes, for the most part, were all military surplus and if it inflated and seemed airworthy, you jumped it. As a civilian, I never gave much thought to the condition of parachutes until about 1966 when I began working as a first jump instructor and started working on obtaining my rigger’s certificate.

In the early days, small clubs sprang up here and there, mostly operating at rural airstrips. Those clubs, many of which sprang up on or near college campuses, consisted of small batches of people who gathered on week-ends to jump together with little attention paid to safety, and they were usually not a formal organization with a charter, and they followed few rules.

You just showed up on Saturday morning with your gear in tow. And if enough people showed up, and you were lucky enough to have talked some local pilot into taking you up, you might get one or two jumps in that week-end, weather permitting.

You pretty much took someone at their word when they told you how many jumps they had or how experienced they were until such time as they did something to prove otherwise. Few people concerned themselves with keeping log books in the early days. Later, log books would become extremely important to validate certain kinds of jumps and what you did during those jumps. Those log books provided places to enter the date, jump number, aircraft type and equipment used, jump altitudes, maneuvers performed and other pertinent information. In time, all of that information, which had to be verified by the signature of another jumper, would be important and needed to obtain certain awards or proficiency licenses. Not having the proper level of licensure could prevent you from performing different types of jumps such as making a demonstration jump or participating in competitions.

My re-entry into jumping after leaving the military was a prime example of how loose things could be. Once home, I got a job and spent my spare time clubbing around at night visiting various honky-tonks on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. At one of those juke joints, The Peppermint Lounge, I met a guy named Rusty and we became immediate friends. The very first time we struck up a conversation, he asked me out-of-the-blue had I ever skydived. I answered in the absolute. He then asked me if I wanted to join him the coming weekend at an “airport” up in Lucedale, Mississippi, about twenty miles away. I gleefully answered that I’d be there bright and early.

That Saturday morning, I showed up at the “airport” which was nothing more than an expansive, scrub field with what appeared to be a ramshackle hangar near the road. Just outside of the hangar sat a dirty, dented small airplane with the right door taken off. Some guy, who turned out to be the pilot, was sitting in the open door of the airplane strumming a guitar and singing twangy country songs to a gaggle of young girls gathered around him. Off to the other side of the hangar were parked four or five cars where a few people were milling about. I parked my car, got out and looked for Rusty.

He hadn’t shown up yet, but one of the people wandering around the cars spotted me and approached. We shook hands. His name was Noel Funchess. He told me, without being prompted, that he was the senior jumper there. I took that as gospel.

In those days, when someone told me that they were a jumper, I pretty much didn’t challenge it unless they were wearing their helmet backwards. I just went along with the program. Shortly, Rusty pulled up and jumped out of his car and began introducing me to some of the others gathered there. “You ready to make a leap?” Rusty asked of me. I answered in the affirmative. He then said, “Let’s find you some gear.”

No one asked me how many jumps I had made. First of all, the jumps I had made were two years prior, and I had only made three sport jumps then. Nowadays, you’re considered a student well beyond your fiftieth jump. Even back then, at the commercial centers, you needed to make at least five jumps with your parachute automatically opened for you by a static-line. And you had to do that well, to your instructor’s satisfaction, before you were allowed to progress on to making free-fall jumps.

Once you were cleared to pull your own ripcord, the routine usually was that you proceeded along a path of making free-fall jumps of varying lengths. For example, once cleared to free-fall, you first made three, five-second free-fall jumps and tried to remain stable throughout. If that was successful, you progressed to making three, ten-second free-falls before progressing to three, fifteen-second free-falls, perhaps trying a turn or two and remaining stable before progressing to making three twenty-second free-falls and so-on until you reached the level of making three, thirty-second free-falls, all very carefully observed and critiqued by more experienced jumpers. Along the way, you were expected to maintain your belly-to-earth stability in free-fall, to be able to hold your heading while falling, counter any spins with the use of your arms and legs, and pull your ripcord smoothly allowing your parachute to open properly. Once under your parachute, the second part of every jump was learning, mostly by trial-and-error, how to control your parachute so that you landed somewhere near a target on the ground.

So there I was with three static-line jumps under my belt several years in the past, and Rusty was off digging up some gear for me – no questions asked. Hell, I didn’t even know what Rusty’s qualifications were or how many jumps he had made.

Shortly, Rusty came along with a main parachute slung over his shoulder, carrying a smaller reserve parachute in his hands. “Here ya go!” Rusty said enthusiastically. Then Rusty said, “Let’s do a thirty second delay.” I took the gear and began putting it on. At least, I remembered how to do that. He had also dug up a helmet that was at least two sizes too big for me. As I put the gear on, I was frantically trying to remember everything that I had learned two years before. That meant that on my fourth sport parachute jump ever, we would exit at 7,200 feet and free-fall for 30 seconds and then I would, hopefully, open my parachute. I said, “Okay.”

Now, if you’ve never jumped, here’s a little reader-participation exercise to give you a very small idea of what free-falling for 30 seconds is like. First, imagine you are falling. Not off of a kitchen chair, mind you. You are at seven thousand feet in the cold, blue sky. (That’s higher than most U.S. mountain peaks.) The air around you may be chilly; the ambient temperature losing three-and-a-half degrees from the temperature on the ground for every thousand feet that the aircraft climbed. So, if it was 70 degrees on the ground when you took off, it will be about 45 degrees at exit altitude. When you exit, you’re in mid-air, nothing around you except sky and possibly a few clouds that may appear as huge masses of dingy, bulbous, white cotton when viewed from the side; the horizon is a flat line where the earth meets the sky and it completely surrounds you; the wind will become a minor hurricane in your ears as you pick up speed in your descent; your body, the motion of your arms and legs are being controlled by gravities pull and the air will be rushing around you at 120 miles-an-hour; you will react as an uncontrolled falling leaf, until, like a swimmer controls the water, you learn to manipulate the air rushing around you using your arms and legs as paddles of a sort. As you fall through the atmosphere, the patchwork quilt of brown-and-green earth beneath you is spread to the horizon in all directions around you. You will have no sensation of height. To be afraid of height requires a reference to the ground beneath you. In free-fall from such a height, those references don’t exist. Now, look at your watch and follow the second hand as it ticks off 30 seconds while holding the vision of falling that I just described. Or better yet, hold the vision and count off thirty seconds by saying to yourself, very slowly, “One thousand…two thousand…three thousand…” and so-on until you reach thirty seconds. You’ll get some sense of how long a 30 second free-fall is. The funny part? It never seems that long when you are in love with skydiving.

Now, here’s what I was about to do that day. I was going to strap on a parachute, actually two of them, that I knew nothing about. I didn’t know who packed them or how long ago they had been packed. There could have been bed sheets or wadded-up newspapers in those containers for all I knew. I was going to get into a raggedy little airplane flown by a pilot who I knew nothing about along with two other jumpers whose qualifications or experience I knew nothing about. Then, I was going to graduate from making three very controlled jumps at 2,500 feet with a parachute that had been automatically opened for me by static-line two years prior, to flinging myself out of that airplane that day at 7,200 feet and flailing around in free-fall for 30 seconds, hoping that when my altimeter read 2,500 feet, I could find a ripcord to pull and save my life. Did I consider the potential consequences of doing any of that? Nope. Not one shred of it. Here’s what I was thinking that day: I’m just going watch the other guys, and do whatever they do. That’s it.

When the time came to exit, it was as if some magical force entered my mind and body. I mimicked every move the other guys did. I was last out, so that gave me an edge in the mimicking department. Upon exiting, they went into a spread eagle. I arched hard and did exactly as they did. I was completely stable – and comfortable.

It was as if I had done it a thousand times. There was an adrenalin rush as I fell but it felt good. I really don’t remember looking at my altimeter. Doing so would have meant taking my eyes off of the other two guys. I remember the rapid rustling of the fabric of my clothes and the rushing sound in my ears. I remember the wind getting underneath my helmet and trying to rip it off. I watched as they both moved their arms inward towards their bodies to grasp their ripcords, and I did the same. As they quickly pulled their arms back out, ripcords in hand, and their parachutes began to open, I copied their movements. It was if I had been born to skydive.

I found my ripcord, pulled it and my parachute opened. I then looked up into a completely foreign scene as I had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to be seeing. Whereas my parachutes at Fort Bragg years before had two slots to channel the air for steering, this one had two large L’s cut from the fabric. But, it was full and round and that’s all I cared about. I reached up and grabbed the steering toggles. Pulling one left would turn me left – pulling one right would turn me right. In no time, I hit the ground hard but was able to stand up immediately. The others came running over to me and we all began rapid-fire chatter about our experience.

The entire act was as natural as breathing. I was elated and hooked even more than before, already planning to go again. And, that’s exactly what I did, weekend after weekend, for the next several months. I started picking up on the smaller nuances of skydiving and got proficient at packing parachutes again. I had earlier learned that skill in my time at Fort Bragg. My mind was at all times filled with thoughts of the next jump. Nothing else mattered. From that day on, everything I did except for eating and having sex revolved around skydiving.

The sport would refine itself over and over in the coming years with more regulations, better equipment, and jumpers who knew that if we were to survive as a sport, we would have to become much more safety-minded and less lawless. That would take time. Today, equipment development has progressed at light speed, with parachutes becoming smaller, lighter and, in some cases, faster and more dangerous. Whereas the older parachutes merely let you down with little directional control, and only progressed in design and function to a slightly better degree when round parachutes were highly modified in the mid to late Sixties, today’s parachutes are square airfoils which mimic an airplane’s wing. They reach much higher forward speeds and are extremely maneuverable. They have to be flown in much the same way as an airplane. Landing accuracy has reached a point where it takes electronic measuring equipment to measure the miniscule distances that define who lands with more accuracy.

Aircraft sizes and capacities have increased to the point where as many as 100 jumpers at a time can exit an airplane nearly simultaneously on one pass, instead of only three or four jumpers at a time as in the past. Even jumpsuits have improved. Additionally, most jumpers wear highly refined automatic openers that will save a life in the event of a mid-air collision or a black out that might incapacitate a jumper. The rules and regulations have increased as well. The United States Parachute Association is located just two hours from where I sit now, and has become a gold standard in how a sport should be run. But that’s now.

The days of seedy airplanes and surplus military equipment and poorly run clubs and drop zones are over. What is not over, if I could again put my feet into the boots of a first-time skydiver, is the thrill, the excitement and the camaraderie of the sport. I don’t think that will ever fade away. I was in the thick of something new, crazy and wild in those days and I was completely captivated by it. I genuinely miss those times and the jumpers I knew then.

In 1966, the Viet Nam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy and a host of other world events would rock our society, and I would barely be aware of it. Neither were my fellow jumpers. We were completely immersed in our own little world.

We ate, slept and breathed rip-stop nylon, airplanes, high altitudes, and landing accurately. And, we had the reputation of being fierce revelers. Few could party as we did.

We were totally wrapped up in the sport and thought about little else. While the world was supposedly falling apart around us, we went on obliviously doing what we loved. I would continue that journey intensely for more than 25 years. No matter where I jumped, there were encounters with memorable characters at every drop zone. They shaped my life and I have never recovered. That is what these stories are about.

To be continued…